Here be dragons

Bobby Neptune turns to Kenya’s wild spaces to heal from a personal trauma, leading him on a journey of internal discovery | Photography by Bobby Neptune

I first heard the words Beyond This Place, Here Be Dragons in an old Sydney Pollack film, where one of the characters warns the other they are in uncharted territory and should be careful. It was used in the context of exploration to make us aware of the unknown.

The second time I came across the phrase was in a US Forest Service fire watch tower, in Northern Montana’s Flathead National Forest, about five miles from the Canadian border. There was a device in the middle of the watch tower that was used to range and bear fire locations. When you turned the device to face toward Canada the maps were blank, and somebody had creatively written ‘Here Be Dragons’ onto the blank spot that made up Canada’s end of the forest. It was a simple and comical gesture referencing back to a generation of exploration that had long past. It was also meant as a joke about the apparent indifference the US Government showed toward a forest fire on Canada’s side of the border.

What I didn’t know at the time was the significance the phrase would play in the coming years of my life, as I started to explore the far reaches of Africa’s wild spaces with my motorised paraglider. And, little did I know that it would continue to teach me the way forward in the midst of my darkest hour.

I first came to Africa in 2008. For someone who grew up on the monotone great plains of middle America, Africa was a departure far from any known constants I could imagine. It was a land of immense colour, contrast, vibrancy, life and death. A place where emotions could run the spectrum from joy and elation to despair and tragedy at a moment’s notice. It was a place that encouraged deep feelings and then went on to destroy them in the same instant.

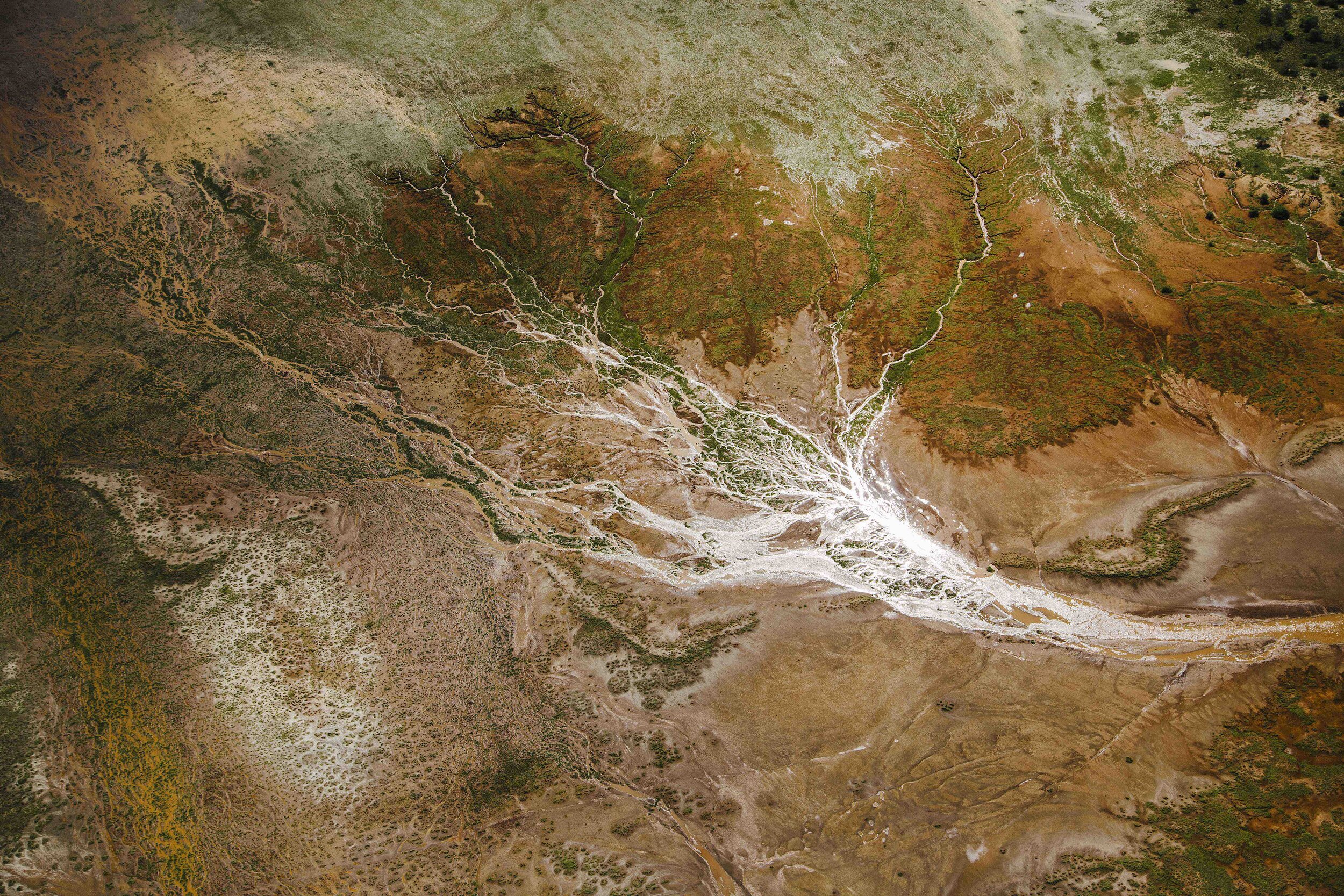

The Ewaso Nyiro River as it deltas into Lake Natron on the Kenya-Tanzania border

Throughout the first half of my photographic career here, I spent my time shooting for NGOs, in conflict zones and in refugee camps. I photographed people in the midst of their own traumas, or filmed them reliving their traumas for whatever story we were producing. I sat behind the camera, somewhat shielded from their own experiences. I was just an onlooker, not a participant. I lived a comfortable life in Nairobi, far from these traumas, and I was always able to maintain enough distance to not live in a constant state of empathic distress.

I would often come back from a week shooting in the refugee camps and drive straight up to northern Kenya. It was my partner, Kim, who introduced me to the wild landscapes of Kenya’s far north; filled with lion, leopard, culture and more than anything, loaded with mystery. Mystery is magnetic to me. I can never get enough. Kim knew it and she constantly planned trips up north. The time in these wild places helped lift my spirits after so much time in the dark corners of the world. They had a sort of rhythm to them, a beating drum of life that reminded me of the way the world was meant to function.

In 2017, Kim and I started to notice large-scale environmental changes occurring. We’d spent so much time in this wilderness that we started seeing small, nuanced signs of change. Then, after a large drought, wildlife numbers plummeted and we saw how long it took for the landscapes to even begin to recover.

We hatched a plan to start photographing these landscapes from above, and looking at the changes and pressures they were facing. We would start with the rivers, then move to the savannahs, then to the mountains. We wanted to photograph it all. A few years prior, I had been trained on a motorised paraglider. My flight experience was fledgling, but enough to get up in the air and look at these same landscapes from above. We started doing a few expeditions. I would fly, she would drive the car. I would land and tell the stories of what I’d just seen. She shared the same sense of adventure, and the siren call of my stories from above drove her mad with jealousy. More than anything, she wanted to be next to me in the air. She wanted to fly.

A few months passed and we were able to get her a tandem flight in western Kenya with one of the top paraglider pilots who was visiting from Europe. Shortly after takeoff, their paraglider crashed in the valley below and both her and the pilot were killed in the accident.

At her memorial, while choking back tears, panic and every other unknown emotion, I told the audience: ‘This is Here Be Dragons territory.’ This is uncharted. This is where none of us have ever walked. The grief, the trauma, the pain, the tears, the loneliness, the isolation. This is our exploration, and it may be the most difficult exploration many of us may ever dare to face. I learned later that trauma and grief are both as much universal as they are individual. By that I mean, many have walked the road before and there are sometimes cairns set by others who have come before you along the trail; but the process is fully unique to the individual. Some days the cairns help; other days they just can’t.

Clockwise from top left: Poling through the mangrove forests of Gazi Bay along Kenya’s South Coast. Home to lots of different bird and fish species, this forest is among the last few left in the region; Shompole Mountain on the Kenyan border with Tanzania. The wetlands in the Shompole ecosystem are formed mainly by the southern Ewaso Nyiro as it drains into Lake Natron; Flamingos above an algae swirl on Lake Logipi in northern Kenya; Evening light cuts through the dust from a herd of elephants moving through the Shompole basin in southern Kenya

For most of us outdoorsy-type of people, there is a siren call toward exploration and adventure. We jump at any chance to put a new pin in the map because, with every external and geographic discovery, there is also a process of internal discovery that coincides. This is why we are always curious about what lies over the next hilltop. It’s never so much about the hilltop as it is about the change the hilltop affects inside of us. For me, exploration is as much an inward looking event as it is an outward looking geographical expedition.

It was Kim who always checked me to make sure I was exploring the mountain ranges of my spirit as much as I was exploring the geography around me. She always asked me to find more of hope, more of joy, more of contentedness. She endlessly and frustratingly pushed me to keep my adventurous spirit in check with the rhythm of my own emotions. How was I going to make a way without her?

In the months that followed the accident, my feet were earthbound and all the stages of grief would become my most unwelcome bedfellows. I left Africa, partly wondering if I would ever come back. I spent time away, I travelled a bit. I did my best to recover. But how do you even begin to make sense of that sort of loss? My counsellor keeps telling me that it takes anywhere between three to six years to properly grieve a loss or recover from a traumatic life-altering event. I think that number is traumatic in itself. Six years is a long time.

Filled with tales of journeys long past, lived on through names littering the trails such as Shipton, Mackinder and Tilman, Mount Kenya’s glaciers will soon join the ranks of folklore as they are receding at unprecedented rates

The one thing I did take from counselling was how important rhythm is in recovery from trauma. I’m not good at rhythm, but I did remember the adventures Kim had introduced me to years before, and how being in wilderness had helped me make sense of my time in the refugee camps. The rhythms I found there were much bigger than me, and helped show me a way forward.

I jumped back into my harness and started flying again. Apprehensively at first, but soon pieces started to come together. I found myself spending as much time as I could on the paraglider, in the most wild places I could get to. One expedition led to another, and I felt some of the weights begin to lift.

In the western world, we control almost everything in our environments. We can change the temperature in our house, we can switch on and off the lights. We can even control what food we eat all year long, because we can ship it around the world on an airplane. We are in control.

Nature provides us with an antithesis to this. When we’re in the wild, we can’t switch on the lights whenever we want. We don’t have control over when the sun rises, or what the temperature is, or what the weather is doing. We don’t have control over the direction the elephants move, or when the lion roars. There is a rhythm of life, death, sunrise and sunset that plays out in the beautiful story narrated by the natural world every day, and there is nothing we can do to control it.

I think part of the problem with being in control of everything is that when something does go terribly wrong, the responsibility of that wrong falls on us. If we buy into the lie that we are in control, then our outcomes are our own responsibility. But if we can concede little bits of our control to the rhythm of the wild, then I think we will find so much more healing in our humility.

The Ewaso Nyiro River winds through the Shompole ecosystem in southern Kenya

In the place where we scattered Kim’s ashes, the wind blows from the east down into the Rift Valley, out across Lake Baringo and up the escarpment on the other side. From there it carries on west to Uganda, then over and through the warm and humid rainforests of Congo, and finally meets the Atlantic Ocean. I assume it spins and tornados through the doldrums, spreading out into a million billion tiny particles as it covers the whole of our blue planet. In the moment we spread Kim’s ashes, they went soaring into this very wind. It was beautiful, and I couldn’t help but think that now nothing would go unexplored. No stone would be unturned and no valley unseen. She is a part of the wind now. Free to run infinite around the world.

That’s how I want to live my life. Not scared that any dragons lie beyond this place, because I‘ve seen for myself. I want to know that internally, just as much as I know it externally. I want to look back on this long life when I’m 80 or 90, and be exhausted by the amount of stories I have lived and the amount of life I’ve experienced. I want to know I made the most of joy, of hope, of sadness, of grief, just as much as I want to swim in all the oceans or see the North Pole.

When a paraglider inflates, the front strings go tight pulling the leading edge into the air. The ram air pockets fill with air and give the paraglider the form of a wing. It’s a rather simple concept. Each time it inflates, I imagine Kim, lifting it up and pushing me toward the sky. I think that’s part of life. We soar on the wings of those who have come before us. Their dragons become our norms. Our dragons become the next generation's starting point.